Observations on an Eclipse

I saw the eclipse. A few millions of my fellow Americans did as well.

I argued and fretted with a company who contracts with me to allow me to arrive about twelve hours earlier than required in order for me to view the eclipse. They fretted and argued back and thus it was that I ponied up the extra $645 to make it to Saint Louis at 9:45, after nearly missing my connection in Atlanta due in part to a cabin attendant who must have been trained by the Gestapo.

I got to the car rental joint and stood in line for forty-five minutes to get my Corolla. 11:21:15 Apparently, I am not the only one who had made an assignation with the moon. Heading south, absent breakfast and lunch, I was contemplating famishment, going through my carry on, one-handedly searching for my emergency strip of wintergreen chewing gum to stave off hypoglycemic coma. I had chosen the hamlet of Festus, Missouri as my goal. Nearly along the line of maximum duration, Festus had the advantage of being off the beaten track. After a short repast at the local Burger King, I made for Sunset Park, attracted by its public status, ease of navigation, and absence of tree-cover.

I chose well. When I arrived at 12:15, a little over an hour before the Event, a few dozen people had already set up. I donned my bona fide sun gazer’s goggles and could already see that a good solid bite had been taken out of the sun’s disk. The air was hot and humid but in my gypsy lifestyle, a large selection of garb is not generally possible. I lounged in my trousers and long shirt on the grass, a victim to small crawly things and sweat. The crowd swelled to maybe three score. Listening to a green-haired siren with a voice that could etch glass, I learned she had driven down with her unfortunately bearded companion from Chicago. She interrogated those within my earshot. The winner of the distance contest was a dark, intense and constantly busy man from Dubai who had set up shop on an abandoned basketball court. I heard Mandarin spoken from a small group behind me. A middle-aged guy with three daughters had brought a Sunspotter Scope, projecting a six-inch image onto a paper screen. He was the star of the show.

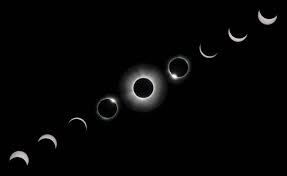

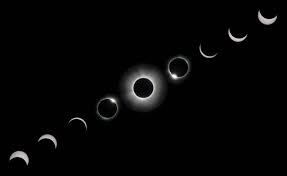

12:47 Closer. The bite had become a gulp and now the slice of the sun is about half gone. Nothing else has changed. The sun feels just as hot. The sweat is as sticky. I lie back to view through my glasses, over-warm but still comfortable except for the sweat. The crowd is no larger even as Sunspotter Man holds forth about sunspots as they are eclipsed. Dubai Guy is quietly busy, taking photos with a large camera, holding his generous sun-filter in front of the lens with each shot. I tried the same with my cell-phone with no success.

13: 15 The slice has passed through sliver to become a serpiginous smiley-face. Cicadas and cricket have started up. It has become cooler, a breeze has sprung up. My place on the grass is quite comfortable. The Mandarin boys are impressed. The light is odd, seemingly just as brilliant but without there being enough to go around. The grass under the trees is dappled with flights of overlapping crescents. The street lights have come on. I turn back to the smiley-face and discover I am wrong. The smiley face is not a smooth line but has become knobbly, the extremites almost like a string of beads, in this case, Baily’s Beads. The sun, shining between the high passes in the mountains of the moon, seen in profile blossom into brilliance along the thin limbs of the decreasing crescent. It is cooler now. Momentarily I am happy for my long-sleeved shirt. A voice over a loudspeaker counts down the last ten seconds to 13:17:07. I watch as the sun’s light is turned down, as if by a rheostat, until it is dark. Inside my goggles, I can see nothing. I rip them off to see the magnificent corona, unsuspected until the last of the last sliver is obscured. It shines out against a dark sky where a few stars peek out. I think I can see Mercury. The light once more has changed, not twilight, odd, the sky still giving it illumination, if only slightly. The corona, a ring around the absolute black of the moon, changes while I watch, almost as if on fire. The loudspeaker cuts in giving a countdown for the last ten seconds to 13:19:45. I regret I did not drive fifteen minutes further to have it last 3 seconds more. The light breaks out as if anxious to escape. Immediately, the light changes again, brightening second by second to what looks, but does not feel, like full sun. People arise and collect their blankets, walking under the hickories and their flights of crescents.

Green-haired Girl and Beard have left Dubai Guy, Sunspotter Man and me to the remainder of the Event. I rise to leave, looking up briefly to see the other parenthesis has appeared, to join, belatedly and unsuccessfully, the first one.

Driving back through the celestially-created traffic jam, I have more than enough time to contemplate. Millions of American have spent the greater part of a day to view a transient solar accident: almost three minutes where we can actually look at our life-giving sun without protection or damage. During any of the other 12,107,280 three-minute periods of my life, looking at the sun for even a few seconds would have struck me blind. Yet, without this deadly irradiation, our world is itself dead, cold, airless, waterless and desolate. When I thought about it, however, we cannot live long on most of this globe we presume to call home. We can stay but hours aloft and mere months afloat without assistance from the smallest portion, dry land. We cannot breathe water, although other creatures do. We cannot even drink from the largest collection of water, it is a poison to humans, driving us mad before we die. Vast portions of the water are unusable even for travel during much of the year, frozen into a hazard we can barely maneuver within. Any water we do drink must be carefully treated and tended lest the effluvia of our fellow creatures kill us.

Air is available in immense quantities without purification or storage, yet a man can walk to the very edge of breathability. We dwell at the bottom of a shallow pool, five miles deep or so, the distance a “wee stretch of the legs” for a fit person.

The inherent hostility of our dwelling, like a hammock over a viper-pit, should be telling us something about the care put into our creation, and upkeep.

‹ Back