The Fourth Wise Man

The Fourth Wiseman

At the very beginning of it all, there had been a round and mostly rotund dozen.

Manachi’s calculation that Jupiter would be in conjunction with Aries in Sagittarius during the coming months had flown through the University like academic wildfire. Every department chairman anted funds up for the huge Expedition, no doubt, from various departmental slush funds. The money was real enough.

However, after interrogating the guides about the risks of the trip, a pall fell upon the community of scholars. The chances of actually arriving at their final destination sobered the department chiefs.

Glory—albeit posthumous glory—had not the caché it once held, huffed the chancellor.

The as-yet-unwritten paper, “Discovery of a New Royal Dynasty by Modern Divination Practices,” lost many of its co-authors overnight. One had to survive to write the paper, they reasoned. One by one, the fat, the pleasure-addicted, and those with more than the usual debts gave their excuses.

Manachi ibn Dooadi, a junior adjunct reader in Astrology, did not drop out. From the beginning, it had been his work that pointed the way, not that the fat and complacent Poohbahs of Ancient Divination, Necrotelemetry, or Acoustical Astronomy ever acknowledged him. Careful calculation of the motions of those wandering planets had shown him the way. It revealed to Manachi the future conjugations, a great Astron in Greek. The heads of departments were so taken by Greek and so bad at the language that they persisted in calling it an aster, a star, despite his many corrections. If it had been a new star, anyone could look up and notice it. This Astron would be infinitely more subtle. Manachi and the University could get in on the ground floor with the new regime.

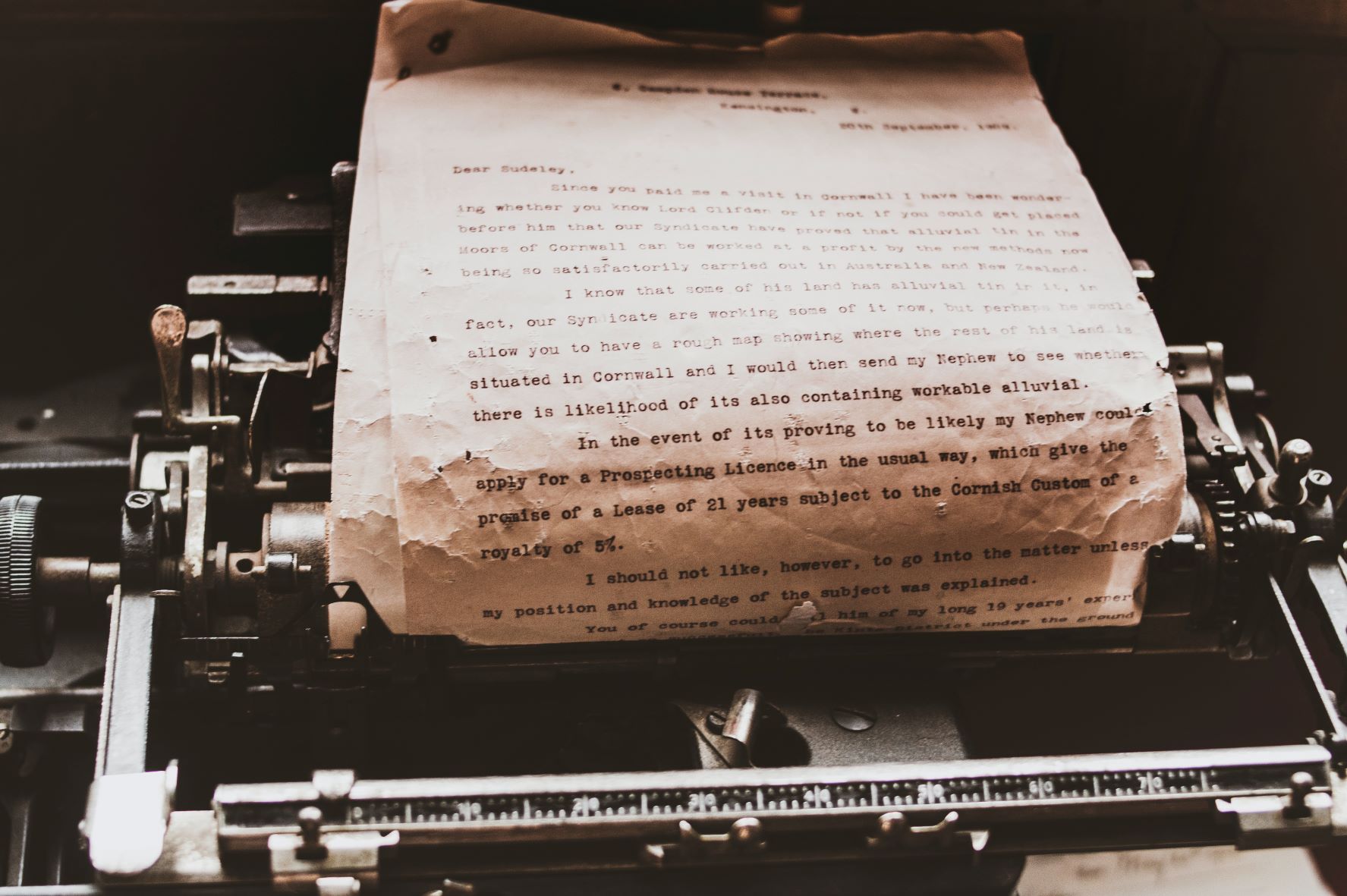

After weeks of bickering, as only wise men can bicker, the team was pared down to the twelve who set out from old Sumer. In the spring, it became clear to Manachi that the last conjunction would occur by the year’s end. Among those departing was Manachi, carrying the new white scroll that had consumed his last drachma. His camel was also the most elderly and least well-tempered of the bunch. Beggars and choosers.

They lost Mechezedeck ab Mafee, Senacabib-Ben Salim, and Haroom ibn Saud that first week when they turned back because of “creative differences with the current leadership of the expedition,” taking camels, drivers, and food with them.

Two more had been left in Agade after they went missing during that performance at Madame Fatima’s Oasis. They sold their camels to the innkeeper. The Great Expedition took their food and prayed for their rapid reappearance.

At Mari, Suleiman ab Tun, the Head of Mathematics, Manachi’s natural ally against the idiocy of Acoustical Astronomy, was lost. Trying his hand at fleecing the local population of its stray coins by matching his statistics with a dice player known as Doc; they would bail him out on their return.

When they reached Aleppo, Waheed ab Asshur, frightened at the loss of colleagues and the decreasing provisions, threw his bones and discovered how inauspicious was the time. Was and had always had been for such an expedition. He publicly marveled how he had not seen it before and headed to his family home in town with profuse warnings and abject apologies for his abandonment.

Each night found Manachi away from the lights of the caravanserai, taking his measurements and entering them carefully on his long scroll. Each night confirmed the impending conjunctions.

They passed through Jericho, hot, humid, at the bottom of the world, awash in date palms and, but for the new royal palaces, grubby. The king was not in residence. The party turned west to begin the climb into the Judean hills. In a final spasm of long days of travel, the remaining five reached a crossroads at Adummim.[1] One well-traveled way led to Jerusalem and the other, a smaller, more rugged trace, led further south. Manachi halted to consult with his guide, Baba the Reliable, deftly avoiding the spittle his camel usually flung at him with each stop or start.

“Why are you stopping, Manachi? We are almost there! The climb’s almost finished. Think! Soft beds and decent food! I understand this Herod fellow is quite the builder; huge palaces, fountains, dancing girls,” boomed the Sisiman ab Wheedle, the Poobah of Improbable Statistics and nominal leader after Suleiman’s imprisonment.

“A palace made even more capacious by Herod killing off his wives and children,” groused Plumbacios ab Kittle, Full Professor of History and grumpy from a persistent saddle sore on a spavined and scholarly behind. He shifted uncomfortably in the saddle until his camel turned to bellow at him.

“Don’t be uncharitable, Professor. Romans are not noted for being the jolly sort, I grant you,” replied Phinn ibn Faisel, Bursar to the college and holder of the Expedition’s purse strings. “Smile and ingratiate yourself if you want to get home from these savage realms.” Phinn’s own camel, ill-tempered at his bulk, made a pass a biting him before being rapped on his snout.

“We do not need to go to Jerusalem, my lords,” squeaked Manachi. Jerusalem is only the current capital. A little reading shows that the founder of their greatest dynasty was born just over that hill, or perhaps the next one. This first hill is not on my map. The guide calls it Herodium, says it was built[2]—but that is nonsense.”

“Quite so, Manachi. Confusing country. Shifting hills, battles lost from epidemics, a single god: crazy, unpredictable. Better to make your observations and skedaddle back to civilization. Herod’s our best bet. Might not take kindly to us slipping in and out, donchakno.”

The road ahead was broad, the travelers poring around the small party like a stone in a stream.

“The second conjunction is going to happen in the southwest, you know. We can save days by going to this Beth Lehem or Ephratah; names seem to change. I guess from so many wars.”

“Second conjunction? I thought this was all about Jupiter and Aries in Sagittarius. How is that to happen again? Nonsense. We need to go on. The spirits of the ancestors have spoken to me,” boomed Lanquid ab Ishnunna, the First Prophet in the School of Necrotelemetry.

“Planets wander, your grace. Thence the name. The first conjugation was in April, and the second is happening now due to a retrograde motion of Jupiter. The subsequent conjugation occurs in January about the 6th. Three conjugations of the king planet with the Israel star in the destiny constellation in a mere six months! Does that not mean anything to you?”

“Then go follow your star.”

“Astron, not aster, gracious lord.”

Ignoring the correction, Languid continued. “The rest of us will go on to Jerusalem. If what you say is right, we will meet again in this Bread Larder place in due time. If not, come to Jerusalem with your information and apologies.” Douda, the Head, geed up his mount, and Plumbacios, Phinn, and Lanquid followed him. Manachi sighed, nodded to his camel driver, and swung the mount south. A few minutes later, they heard a pounding on the road in the twilight and stopped to face this new challenge with knives drawn.

Over the slight rise, Phinn, his camel at an uncharacteristic trot, slowed and came alongside.

“Don’t say anything, young Manachi! I must be having an attack of foolishness. Perhaps it is better to stick with a fool with sincere vision than fools with self-imposed blindnesses. I gave over the purse. We are near penniless—but lead on young Manachi. Show me your newborn king.” He started to laugh. It was well deserved. How could a baby be born a king? But, it was what the stars had shown to him. He was merely their servant. He made no answer to the still-chuckling Phinn before checking to see that his precious scroll was carefully stowed next to his right leg across the top of the jostling saddle.

They arrived at Beth Lahem, finding it strangely crowded. Once more, they bivouacked out of town in the cold Judean night rather than fight for the last louse-infested bed. Baba went looking for food to break their fast, and Manachi accompanied him. Hunting for kings could be best done in the light of morning.

Before entering the town proper, however, a small light caught Manachi’s attention on his left, seeming to come from a cliff. Manachi walked over while Baba bustled on. Cries of pain greeted him. Screams and waves of cold air emanated from a crack in the cliff. Manachi went on to investigate, drawing his knife. The cleft in the rock that had emitted the light widened out into a small cave, stalls jury-rigged for various beasts. The light came from a fetid corner, only recently vacated by a cow suffering from scour.

“Who are you? Said a big man, blocking his view of a young woman, a very young woman, obviously in distress. “The innkeeper said we could stay here.”

“Pardon me, good man. Are you the girl’s father? Husband? I heard her cries. It’s frigid here.”

“Who I am makes no nevermind, Stranger,” he said with some vehemence. “Leave us.”

For some reason, it became clear in an instant. The man was frightened for the girl. He knew nothing about birthing in women—but Manachi did. He had penned the treatise, “On the Birthing of Babies with a Record of One Hundred Observed Deliveries,” just the year before. The work had gone mostly ignored.

“I can help you. Your wife needs a fire and some clean hands. Here, go purchase some charcoal and start a fire.”

“We are warm enough, Stranger.”

“You may be, but your new wet, naked, infant ‘stranger’ will not be. Go. Do some good for your wife.”

The man left with a grunt, and Manachi turned to the girl. “He is your husband, is he not?”

She nodded.

“First babe?”

A nod

“Only one?”

Another nod.

“Let me feel your belly.”

One more nod.

She was in very active labor, the head engaged, and delivery was imminent. Why was he doing this? The pathetic little family would be even poorer tomorrow with one more mouth by morning. Why did he care? In the morning, he had to find a newborn king.

The man, the girl who had called him Joseph, returned. The sound of flint on steel sounded to little effect as the girl grunted during and panted after each spasm. She was becoming exhausted, and with her, the child. Delivered into a cold cave, the baby would die without a fire.

“Here, use this,” said Manachi, thrusting his precious scroll into the man’s hand. “Start the fire with this!”.

Soon a fire burned inside the stone manger, warming the space wonderfully. Manachi doused his hands in wine. He had seen that done. He eased the head under, catching the small body as it followed almost precipitously. Within minutes, the babe was wrapped in clean rags and placed in another manger.

The baby seemed to glow—the glow slowly—very slowly fading as Manachi watched. The child’s eyes were open, watching him. He felt them study him for long moments before the face, the glowing face, smiled.

Manachi was momentarily lost in the gray eyes, seeming to see the melody of the universe as if he were among the stars. Breaking away only with difficulty, he said, “You have a wonderful child. Keep him safe. Others will come; ask for gifts! They will give them to you once they see him. They will sell their souls to give him gifts. I must leave to find my companions.”

“Thank you, said the girl.”

“No. No. No. It is I who should thank you.”

‹ Back

Comments