The Politics of Sails and Sea-Anchors

I read incessantly as a young teenager. During a strange ellipsis when I should have been reading Lord Jim in Mrs. Nelson's English class at Upper Moreland Junior High School, I read two stories, instead. That fine lady and fine institution of learning have passed to the grave and the wrecking ball. They, as well as those two stories, have left a lasting impressions on me.

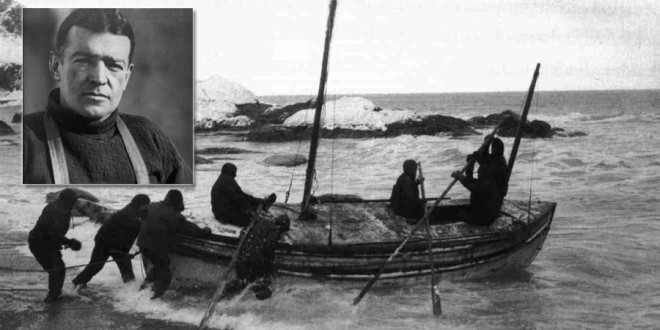

The first narrative was Shackleton's Valiant Voyage,[1] a brief retelling of an ill-fated 1914 Antarctic expedition. Ernest Shackleton and his small party managed to survive a shipwreck in the Antarctic ice pack. After months of bivouac on open sea-ice and days rowing to a deserted island, they determined their best chance of rescue lay with contacting the whaling station on South Georgia Island, 800 miles away across the infamous South Atlantic Ocean’s “Furious Fifties.”

Six men, sailing in a twenty-foot open boat in epic bad weather accomplished the feat, braving almost continuous storms along the way. After landing on the leeside side of the island, they climbed through unexplored mountains to reach the station after a single continuous thirty-six hour trek. The entire crew survived due to their grit, cleverness, and a dogged refusal to give over to what looked like insuperable odds.

During the dangerous open ocean voyage, their tiny craft, lashed by giant seas that threatened to sink it, resorted to a sea-anchor, a drogue on a long line. Attached to the bow and dragging behind the ship as it was pushed backward by the wind, the sea-anchor guaranteed the bow always faced into the wind and waves.

The second story, Brightside Crossing,[2] is a classic science-fiction short story by Alan E. Nourse. Even while the first story was set in the coldest place on earth, Brightside Crossing was set in the hottest place in the solar system. Telling the tale of another failed expedition, Nourse narrates the fictional tale of an attempt to transit the planet Mercury during perihelion, its closest approach to the sun, making it the hottest place in the solar system.

The "sail” and the “sea anchor" in this tale are not parts of a ship but personalities within the expedition. Claney, an adventurer-spaceman and sole survivor of the ill-fated attempt, relates the tension within the expedition, centering on two characters, McIvers and Major Mikuta. While McIvers lobbies for speed, tempting error from exhaustion, and equipment failure, Major Mikuta, the expedition leader, is more concerned with enforcing caution to forestall disaster.

Ultimately, the planet itself determines the men's fate, tipping them into a crevasse of molten tin. Claney survives and retreats along the already explored safe-route, living to tell the tale to a company of fellow adventurers. His listeners conclude that McIvers' aggressiveness was to blame for the failure. Claney, however, will have none of it, asserting that McIvers was a necessary part of the team. McIvers' aggressiveness kept them on schedule even while the Major's caution avoided catastrophe. Instead, Claney summed up their failure as "(W)e just didn't know what we were fighting. It was the planet that whipped us…"

The two stories are the same. Heroic deeds are dangerous affairs. If it were easy, everyone would be doing it. Yet, in the extremity of human actions, sails and sea anchors are each necessary. McIvers' energy, a sail if ever I saw one, was crucial to the expedition's success, even if that goal was unwinnable. Major Mikuta' s success, measured in disasters that did not happen, is less apparent but just as real..

Given the appeal of canvas hardened to a taut curve of urgency by a freshening wind from off the starboard beam, sails have glamour. Yet, on stormy seas, sails are reefed and sea-anchors set out to keep the bows facing adversity. Both derring-do and caution are necessary for success. Failure of one or the other leads to disaster

Yet it is the McIvers of the world who get all the credit while the Mikutas, despite repeatedly avoiding disaster, do not. Innovators, pioneers, and reckless generals are given much ink in what passes for History. Those who slowed down or thwarted feckless and foolish campaigns, who refused to gamble on the lives of innocents and closed the public purse strings to adventurers and con-men, have no statues erected to them. History, in retrospect, usually vilifies them as stuffy fossils of a bygone era and consigns them to the "ash bin of history.”

America is, and always has been, in a similar situation. We, the American experiment, are perpetually determining whether "a nation so conceived (in liberty) and so dedicated (to the proposition that all men are created equal) may long endure." It is a dangerous and inscrutable journey—and always has been. Fools and historians imagine that America walks a bright path to a knowable future. They are in good company as revolutionary governments always think they have discovered that bright path. They are always wrong.

Whatever else we may be, the United States was the first and, so far as I can tell, the only successful revolution the world has ever seen. Political revolutions are uniformly betrayed, the "freedom fighters" of yesterday deciding, after they have eliminated the bloated ruling classes, that the old guys had excellent taste in architecture, food, and women, and make themselves at home in ready-made decadence. This was undoubtedly true for France's revolution of 1789. Conceived in "Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity," the Revolution birthed the guillotines of the Terror and the caprice of mob rule. Dying a mere decade later, a bloody empire rose from the corpse. The emperor's downfall at Waterloo re-established the monarchy—full circle in twenty-six years. Vladimir Lenin's, Mao Zedong's, and Zapata's revolutions, just as sanguinary and destructive, like all such revolutions, have failed or been subverted—all except the American.

The American Revolution was different in many ways, and speculation as to its success is ongoing. However, this I have noticed: while all other modern revolutions claim to be transformational, the American founders never proclaimed how America should be transformed. They claimed rights from an eternal God as the basis for their self-determination, but offered no political theory dictating how their newly freed selves should remake themselves. The French, just a few years later, and all the Marxists thereafter, have prescribed transformations that the people who actually fought the revolution are now compelled to follow, trading one set of shackles for another.

A sample of preambles from the revolutionary constitutions demonstrates:

1) Revolutionary republics are incredibly verbose. Norway (a limited and constitutional monarchy) has a preamble which consists of a single sentence. North Korea's is a page long; China's triple that.

2) Revolutionary republics never fail to proclaim the country is under new management using whatever philosophical dialectic of convenience they can bring to bear. China's preamble is a monstrosity of a history lesson with the people (the ones Mao killed off with such wild abandon once he was in power) as hero/victim.

3) Revolutionary republics uniformly demonstrate a cult of personality. China's mentions Mao Zedong as their savior. North Korea's first sentence ascribes all the success to Kim Il Sung. Cuba's lauds Marx and Engel, who did not fight for Cuban independence, even as it fails to mention America's donations of blood and treasure for their liberation in 1895.

The preamble to the American Constitution, older by centuries than the examples above, appears to be disinterested in either preaching the past, pontificating on the present, or predicting the future. There is no attempt to proclaim what new golden path of enlightenment the new nation is supposed to be following. In truth, the Constitution is rather pathetically prosaic. It merely declares its aim: "…to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defenses, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty…" There is not a single person's name is in the entire document. It expounds no political philosophy and provides no history lesson. Moreover, at some seven thousand words, America's Constitution is one of the briefest in history.

While believing to a man that Man was perfectible, the American founders did not presume to specify how to go about engineering that transformation—leaving that to the Man himself, it is supposed. Instead, they were convinced that people would remain, for the moment at least, avaricious, power-hungry, and self-serving—and writing a constitution to thwart these baser tendencies.

Thus, like all intrepid voyagers over unknown dark seas fraught with perils and sudden calamity, the founders fashioned a political structure with both sails and sea-anchors. Those good men, sweating through a summer in Philadelphia, wanted above all to have stability—they wanted America to stay afloat. Having just removed the shackles of a millennium-long monarchy, they wanted no part of any hereditary oligarchy. Yet, they were at least as dismayed with instituting “mob rule,” what we would call “pure democracy.”

After a careful historical study of failed democracies through history, James Madison wrote in the Federalist Papers, "In all very numerous assemblies, of whatever characters composed, passion never fails to wrest the sceptre from reason."  “Pure democracy," susceptible to demagogues and careless of personal rights and liberties, is as much to be feared as the distant capricious rule of an autocrat. As heterogeneous a bunch of men as the nation could put into a single room, the founders fixated on political “stability” as being the more valuable for the nation—rather than “progress.” Even as they engineered how inscrutable desires, unforeseen circumstances, and future philosophies must be allowed to change the nation through law, they placed out two sea-anchors: "Separation of Powers" and "Checks and Balances." Both of these mechanisms have come under withering criticism of late for obstructing "true democracy" by limiting government and “the will of the people.”

“Pure democracy," susceptible to demagogues and careless of personal rights and liberties, is as much to be feared as the distant capricious rule of an autocrat. As heterogeneous a bunch of men as the nation could put into a single room, the founders fixated on political “stability” as being the more valuable for the nation—rather than “progress.” Even as they engineered how inscrutable desires, unforeseen circumstances, and future philosophies must be allowed to change the nation through law, they placed out two sea-anchors: "Separation of Powers" and "Checks and Balances." Both of these mechanisms have come under withering criticism of late for obstructing "true democracy" by limiting government and “the will of the people.”

It is well-deserved criticism and one of which the founders would be infinitely proud, I believe. They viewed “true democracy” with unalloyed suspicion. Despite its popularity, enthusiasm, and innovation, the natural history of pure democracy is, like a a compass needle, after swinging back and forth, it unerringly leads to excess and self-destruction. It is inevitable that the majority will impress its will on the minority—unless thwarted.

Over the last two years of divided government, political inanition has been real, frustrating, and politically salutary. Madison would again be pleased. Despite vitriol, violence, attempted murder of elected national officials, political machinations which would have made our ancestors blush, and fulminations about basic changes to the political make-up of the republic, no grotesque violation of the rights of Americans has occurred. Instead, the system acted in the way it was intended to act and, despite every daft idea getting its full fifteen minutes of fame, the mob passed no wildly popular (but ultimately destructive) law. Success!

Political upheaval occurred. Despite the popularity of radicalism, the danger of political street violence, and the feckless flaccitude of our "leaders," the sea-anchor held. No guillotines were erected. No one fired on a later day "Eastern Star," and no one declared a new republic [3]

The judiciary, especially the Supreme Court, acts as a sea anchor, preventing the House from sailing away with the ship of state. Tasked with upholding the Constitution, the judiciary is obligated to deal with what has been written, not what they wish had been written. We are currently in an era which denies the need for courts to be sea anchors. As “war is diplomacy by other means,” the courts have become “legislation by other means.” Since the sixties, the courts, consisting of small number of unelected and unremovable professional jurists, have written law. Not infrequently, their judgments are in abject violation of the plain reading of the Constitution and particularly the Bill of Rights. Instead of being committed to their oaths to uphold the Constitution, politicians are demand they be selected to be "representative," "balanced," or, worse of all, emulative of a newly-dead member, a kind of judicial re-incarnation.

It won’t wash. Sails and sea-anchors are both necessary for any successful expedition or endeavor. One-party rule in the House is inevitable—elections make winners and losers. Thus, a "sail" will always be available to the republic. "Sea-anchors," so easily disdained and their successes so frequently hidden, are the perpetual targets of political “sails”—the two are entirely antithetical in both purpose and mechanism.

Turning the courts into “legislation by other means” will be disastrous.

The Supreme Court of the United States must always keep its oath to defend the Constitution, to resist the changes that the society demands of its representatives. Rather than attempting to make the courts look like the House, we need to ensure that the courts look like the Constitution.

To repudiate the constitutional safeguards is to invite disaster, chaos, and injustice.

[1] [1] Alfred Lansing, Scholastic Book Services, 1962

[2] Nourse, Alan E., Galaxy, Vol11, No. 3, January 1956

[3] I discount Seattle and the Antifa squatters’ camp. While their aspect is of a new-age reincarnation of the "blackshirts," in reality, once their mothers had had a chance to fumigate the basements, the little darlings all went home to them.

‹ Back

Comments